Published: Jan 25, 2013

Carl Menger – Principles of Economics (1871) 2 – Chapter VIII: The Theory of Money:

“In the early stages of trade, when economizing individuals are only slowly awakening to knowledge of the economic gains that can be derived from exploitation of existing exchange opportunities, their attention is, in keeping with the simplicity of all cultural beginnings, directed only to the most obvious of these opportunities. In considering the goods he will acquire in trade, each man takes account only of their use value to himself. Hence the exchange transactions that are actually performed are restricted naturally to situations in which economizing individuals have goods in their possession that have a smaller use value to them than goods in the possession of other economizing individuals who value the same goods in reverse fashion.

… The direct provision of their requirements is the ultimate purpose of all the economic endeavors of men. The final end of their exchange operations is therefore to exchange their commodities for such goods as have use value to them. The endeavor to attain this final end has been equally characteristic of all stages of culture and is entirely correct economically. But economizing individuals, would obviously be behaving uneconomically if, in all instances in which this final end cannot be reached immediately and directly, they were to forsake approaching it altogether.

… He would therefore make the marketing of his commodities either totally impossible, or possible only with the expenditure of a great deal of time, if he were to behave so uneconomically as to wish to take in exchange for his commodities only goods that have use value to himself and not also other goods which, although they would have commodity-character to him, nevertheless have greater marketability than his own commodity. Possession of these commodities would considerably facilitate his search for persons who have just the goods he needs.”

The most basic trade is one where two individuals prefer to have, for their personal consumption, what the other has.

Besides trading what you have for what you would rather have, you can also trade what you have for something you can more easily trade for what you would rather have. This means you trade something that you are not interested in consuming yourself for something you are also not interested in consuming yourself. In deciding what to accept in this kind of trade, you must evaluate all the elements that make it more or less difficult to sell, and at what price, and compare that to the good you are considering trading away.

These elements are:

Its marketability for personal consumption

The ease with which it can circulate between individuals who do not consume it

The costs that are brought about due to its physical makeup

Principles of Economics – Chapter I-2: The Causal Connections Between Goods:

“Our well-being at any given time, to the extent that it depends upon the satisfaction of our needs, is assured if we have at our disposal the goods required for their direct satisfaction. If, for example, we have the necessary amount of bread, we are in a position to satisfy our need for food directly.

… The same applies to all other goods that may be used directly for the satisfaction of our needs, ..

But we have not yet exhausted the list of things whose goods-character we recognize. For in addition to goods that serve our needs directly (and which will, for the sake of brevity, henceforth be called “goods of first order”) we find a large number of other things in our economy that cannot be put in any direct causal connection with the satisfaction of our needs, but which possess goods-character no less certainly than goods of first order. In our markets, next to bread and other goods capable of satisfying human needs directly, we also see quantities of flour, fuel, and salt. We find that implements and tools for the production of bread, and the skilled labor services necessary for their use, are regularly traded. All these things, or at any rate by far the greater number of them, are incapable of satisfying human needs in any direct way—for what human need could be satisfied by a specific labor service of a journeyman baker, by a baking utensil, or even by a quantity of ordinary flour? That these things are nevertheless treated as goods in human economy, just like goods of first order, is due to the fact that they serve to produce bread and other goods of first order, and hence are indirectly, even if not directly, capable of satisfying human needs.”

An individual acts to improve his state of being as compared with not acting.

A good is something from the external world that improves the state of being of an individual, as perceived by the individual. A higher order good is something that helps produce the good that can be used by the individual for his perceived improvement.

First order goods are traded on the market because there are individuals who seek them. Because of the demand for first order goods, there is a demand for higher order goods, and this is why they are produced and traded on the market.

Principles of Economics – Chapter VII-2: The Marketability of Commodities:

“..the obvious differences in the marketability of commodities is a phenomenon of such far-reaching practical importance, the success of the economic activity of producers and merchants depending to a very great extent on a correct understanding of the influences here operative, that science cannot, in the long run, avoid an exact investigation of its nature and causes. Indeed, it is also clear that a complete and satisfactory solution to the still controversial problem of the origin of money, the most liquid of all goods, can emerge only from an investigation of this topic.”

Principles of Economics – Chapter VII-2-B: The different degrees of marketability of commodities:

“The first cause of differences in the marketability of commodities we have thus seen to be the fact that the number of persons to whom they can be sold is sometimes larger and sometimes smaller, and that the points of concentration of the persons interested in their pricing are sometimes better and sometimes less well organized. … The second cause of differences in the marketability of commodities is thus the fact that the geographical areas within which their sale is confined are sometimes wider and sometimes narrower, and that while there are many trading points within this area at which some commodities can be sold at economic prices, there are only a few such points in the case of other commodities. … The third cause of differences in the marketability of commodities, then, is the fact that the quantitative limits of the amounts of them that can be sold are sometimes wider and sometimes narrower, and that within these limits the quantities of some commodities brought to market can easily be sold at economic prices, while this is not true of other commodities, or at least not in the same degree. … The fourth cause of differences in the marketability of commodities is thus the fact that the time limits within which commodities can be sold are sometimes wider and sometimes narrower, and that within these limits some commodities can be sold at economic prices at any time, while others can be sold only at more or less distant points in time.”

Goods vary in difficulty in finding someone to trade them with, for use by them. A good can have a high demand or a low demand for consumption, be sold widely or sparsely, and be sold frequently or infrequently.

Principles of Economics – Chapter VII-2-C: The facility with which commodities circulate:

“Some commodities have almost the same marketability in the hands of every economizing individual. … However saleable commodities of this kind may be in the hands of their producers or certain merchants, they lose their marketability altogether, or at any rate in part, if even a suspicion arises that they have already been used or only been in unclean hands. They are therefore not suited in economic exchange to circulate from hand to hand.

Other commodities require special knowledge, skills, permits, or governmental licenses, privileges, etc., for their sale, and are not at all, or only with difficulty, saleable in the hands of an individual who cannot acquire these requisites. In any case they lose value in his hands. … Hence they are as little suited as the commodities of the previous paragraph to free circulation from hand to hand.

Moreover, commodities that must be specially fitted to the needs of the consumer to be useable at all are not saleable in an equal degree in the hands of every owner. … ..especially since these businessmen generally have facilities for fitting the commodities to the special needs of their customers. In the hands of another person, these commodities can be sold only with difficulty and almost always only at a heavy loss. These commodities too are not suited to free circulation from hand to hand.

Commodities whose prices are not well known or subject to considerable fluctuations also do not pass easily from hand to hand. A purchaser of such commodities faces the danger of “overpaying” for them, or of suffering a loss before he has passed them on due to a fall in price. … ..commodities that are subject to violent price fluctuations can circulate easily only “below the market,” since all persons who are not willing to speculate will want to protect themselves against loss. Thus commodities whose prices are uncertain or fluctuate severely are also not well suited to free circulation from hand to hand.

Thus we find that for a commodity to be capable of circulating freely it must be saleable in the widest sense of the term to every economizing individual through whose hands it may pass, and to each of these persons it must be saleable, not in one respect alone, but in all four of the senses discussed above.”

Goods vary in difficulty in finding someone to trade them with, for further trade by them. A good held by different people can attain the same market price or different prices. A good may require a special skill or license to be sold. A good may be subject to considerable fluctuation in price, which makes people who are unwilling to speculate on it only willing to pay a conservative price for it. Technological evolution is one reason why many consumer goods face quickly eroding market prices.

The different chemical elements that exist on earth have a wide range of activity at the current temperatures and pressures that we experience. They react to varying degrees to exposure to air, such as bursting into flames or corroding. Some are a solid, some are a liquid, and some are a gas. Some are dangerously radioactive.

Most chemical elements have found their way to be useful in the production of goods. Because of the different kinds of activity, they bring with them different amounts of costs to keep them useful during transportation and storage. There are differences in the costs of discovering what the element is, and of which purity it is. There are differences in the costs of dividing up or combining an amount of elements.

Speculation – Jeffrey Herbener explains Rothbard (2012-03-10) 3:

“..when Rothbard theorizes about speculation, we can usefully break his treatment into these categories. He first points out how speculation works for the individual person. The individual person is speculating with respect to the future, about the outcome of his own actions. The second category is speculations that a person makes about the actions of others that he intends to interact with. So this is where we get the market. And within that category he talks about speculation that people make on their own about what others will be doing in the market; predicting what prices will be and so on. And then he talks about speculation by the specialists in the market; they’re predicting on behalf of other people the speculative outcome of even other people’s actions.

Now the way this plays out in Man, Economy, and State is as follows. So we get this first point that all action is speculative, on page 6. Very early on, this is part of the general theory of human action; it doesn’t apply to pricing per se. But Rothbard carries this through to the section on pricings. So when we get to the section on pricings, with demand and supply, he explicitly points this out. He says: ‘Both demand and supply are speculative’. When a person has a preference rank and they say ‘I prefer an Ipad 2 to 500 dollars’, both those entries in the preference rank are speculative. The person doesn’t know before getting the Ipad 2 and using it to attain his end, what the realized value of having the Ipad 2 is. He doesn’t know until he gives up the 500 dollars, what exactly the opportunity cost is that he foregoes in the future.

So speculation is in the very formation of demand and supply. He builds this into his pedagogy when he develops his presentation of demand and supply with the total stock, total demand analysis. So here he’s not just trying to show that prices must, of necessity, be determined just by preferences, but he explicitly brings out the speculative element in that presentation.

So the conclusion from this, of course, that he arrives at, is that prices themselves, both the level of prices in markets, and changes in prices that come through shifting demands and supplies, both of these things are speculative. Prices themselves are not like facts of nature; they’re results of human action that are based upon speculation.”

Reality is incredibly complex. In order to attain our ends, we must make predictions about the future and the effects of our possible actions, and choose among them.

A price is an exchange ratio of a trade that took place between two people. A price is the result of a bidding process 4, which involves two or more people. A bid is based on an individual’s goals, his understanding of the world, and his predictions about the future, all of which are changing as time goes by.

An economy is made up of individuals seeking their personal goals. For these ends they require goods; most of which are produced by others. In a monetary exchange, an individual trades away something he does not intend to use for another thing he does not intend to use. This means he must consider the value of the good to other people, which relates to how the good in the future can help other people attain their goals.

Menger emphasizes this point of a money good as a consumer or producer good in the appendix:

Principles of Economics – Appendix J: History of Theories of the Origin of Money:

“I refer to the observation that the character of money as an industrial metal often completely disappears from the consciousness of economizing men because of the smoothness of operation of our trading mechanism, and that men therefore only notice its character as a means of exchange. The force of custom is so strong that the ability of a metal used as money to continue in this role is assured even when men are not directly aware of its character as an industrial metal. This observation is entirely correct. But it is also quite evident that the ability of a material to serve as money, as well as the custom on which this ability is founded, would disappear immediately, if the character of money as a material applicable to industrial purposes were destroyed by some accident. I am ready to admit that, under highly developed conditions of trade, money is regarded by many economizing men only as a token. But it is quite certain that this illusion would immediately be dispelled if the character of coins as quantities of industrial raw materials were lost.”

In the first part of this article I expounded on Menger’s theory of money. In this part I will critique Rothbard’s theory of money (Rothbard is a follower of Ludwig von Mises on money, as far as I know), then I will apply Menger’s theory to fiat money, and lastly I will comment on the Bitcoin phenomenon based on what I have written up to that point.

Murray Rothbard – Man, Economy, and State (1962) 5 – Chapter 3-2: The Emergence of Indirect Exchange:

“As the more marketable commodities in any society begin to be picked by individuals as media of exchange, their choices will quickly focus on the few most marketable commodities available. .. It is evident that, as the individuals center on a few selected commodities as the media of exchange, the demand for these commodities on the market greatly increases. For commodities, in so far as they are used as media, have an additional component in the demand for them—not only the demand for their direct use, but also a demand for their use as a medium of indirect exchange. This demand for their use as a medium is superimposed on the demand for their direct use, and this increase in the composite demand for the selected media greatly increases their marketability. .. The process is cumulative, with the most marketable commodities becoming enormously more marketable and with this increase spurring their use as media of exchange. The process continues, with an ever-widening gap between the marketability of the medium and the other commodities, until finally one or two commodities are far more marketable than any others and are in general use as media of exchange.”

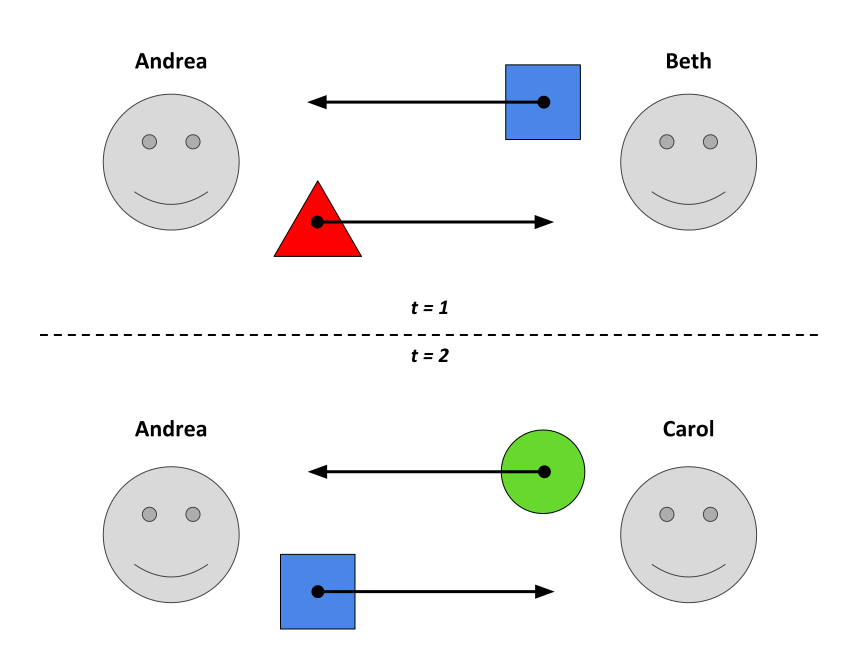

Here is a figure that shows an indirect exchange (Rothbard uses a similar one):

Andrea has a triangle and wants a circle. Carol has a circle but does not want a triangle. Andrea accepts as payment for her triangle a square from Beth, because she knows Carol wants a square. According to Rothbard, Andrea’s demand at t=1 for a square represents an added demand for squares in the market. However, at t=2 Andrea puts the square back in the market. Andrea’s demand for a square is predicated on Carol’s demand for a square. If Carol wants just one square then Andrea can only perform this indirect exchange once. Regarding Andrea’s purchase of a square as a necessary increase of demand for squares would be a mistake.

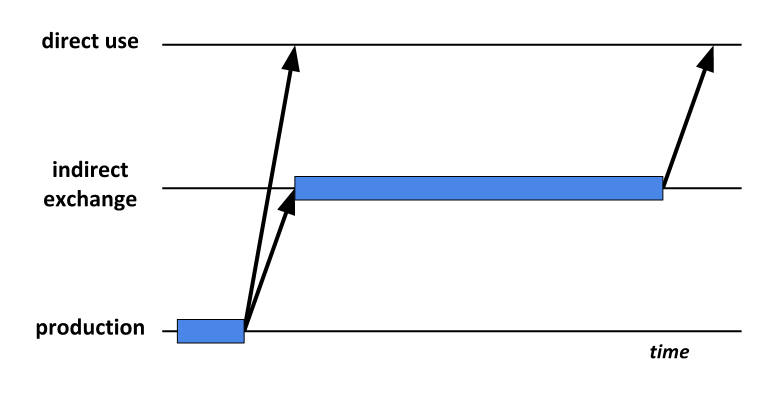

An indirect exchange is an interjection into the production and consumption cycle. The acquisition is based on an anticipated future demand. There is an increased number of buyers, but each of those buyers are buying with the purpose of selling. This means it is a form of arbitrage: the buyer is speculating on getting a higher return at a point in the future than what he is putting in now, from his own subjective value point of view.

Man, Economy, and State. Chapter 4-5-A The Marginal Utility of Money:

“Under a system of barter, there would be no analytic difficulty. All the possible consumers’ goods would be ranked and compared by each individual, the demand schedules of each in terms of the other would be established, etc. Relative utilities would establish individual demand schedules, and these would be summed up to yield market-demand schedules. But, in the monetary economy, a grave analytic difficulty arises.

To determine the price of a good, we analyze the market-demand schedule for the good; this in turn depends on the individual demand schedules; these in their turn are determined by the individuals’ value rankings of units of the good and units of money as given by the various alternative uses of money; yet the latter alternatives depend in turn on given prices of the other goods. .. But how, then, can value scales and utilities be used to explain the formation of money prices, when these value scales and utilities themselves depend upon the existence of money prices? …

Whoever spends money to buy any good or service ranks the marginal utility which keeping the money has for him against the marginal utility of acquiring the good. These value scales of the various buyers and sellers determine the individual supply-demand schedules and hence all money prices; yet, in order to rank money and goods on his value scale, money must already have a marginal utility for each person, and this marginal utility must be based on the fact of pre-existing money prices of the various goods.”

If an indirect exchange is predicated upon future anticipated demand, and doesn’t represent an added demand in itself, then pricing follows a speculative pattern.

In a lecture on conservation and property rights, Rothbard has noted:

“The value of that copper mine as a whole is the discounted future returns. These future returns are brought back by the market into the current capital value.”

I think the pricing of copper coins works the same way.

Carl Menger, Principles of Economics, Chapter VIII-1 The Nature and Origin of Money:

“..the actual performance of exchange operations of this kind presupposes a knowledge of their interest on the part of economizing individuals. For they must be willing to accept in exchange for their commodities, because of its greater marketability, a good that is perhaps itself quite useless to them. This knowledge will never be attained by all members of a people at the same time. On the contrary, only a small number of economizing individuals will at first recognize the advantage accruing to them from the acceptance of other, more saleable, commodities in exchange for their own whenever a direct exchange of their commodities for the goods they wish to consume is impossible or highly uncertain. This advantage is independent of a general acknowledgement of any one commodity as money. For an exchange of this sort will always, under any circumstances whatsoever, bring an economizing individual considerably nearer to his final end, the acquisition of the goods he wishes to consume. Since there is no better way in which men can become enlightened about their economic interests than by observation of the economic success of those who employ the correct means of achieving their ends, it is evident that nothing favored the rise of money so much as the long-practiced, and economically profitable, acceptance of eminently saleable commodities in exchange for all others by the most discerning and most capable economizing individuals. In this way, custom and practice contributed in no small degree to converting the commodities that were most saleable at a given time into commodities that came to be accepted, not merely by many, but by all economizing individuals in exchange for their own commodities.”

Under a system of property rights, the advantage of the concept of indirect exchange is discovered by a few individuals and then emulated by everyone else as they observe their success with it. At that stage, all market participants are involved in the speculative process of medium of exchange selection and pricing (creating stability).

Principles of Economics, Chapter VIII-2 The Kinds of Money Appropriate to Particular Peoples and to Particular Historical Periods:

“..precisely because money is a natural product of human economy, the specific forms in which it has appeared were everywhere and at all times the result of specific and changing economic situations. Among the same people at different times, and among different peoples at the same time, different goods have attained the special position in trade described above.”

Economic conditions change, and with it, the money changes. Despite all this, governments find their way to radically change this process.

Under free markets, indirect exchange develops between the production stage and the direct use stage. Production is oriented towards future consumption, and so is indirect exchange.

Instead of taxing from the market the money that the market itself has selected, a government can require in payment specially designated items that the government itself is the producer of. Economizing on future industry can get completely displaced by a system of tax credits, as far as money activity goes. Government workers earn directly in these tax credits, which non-government workers have to trade real wealth and services for in order to get them.

In all the following situations is possession then required, for turning them over to the government: income tax, capital gains tax, corporate tax, property tax, inheritance tax, expatriation tax, transfer tax, wealth tax, value added tax, sales tax, excise tax, tariffs, license fees, and any services that government provides.

Governments will make the private production of the previous market money illegal, leaving as only alternative using the government tax credits (fiat money). In the real world this process from market money to government money happens gradually. First a 90% government gold coin is set as legal tender, then an 80%, etc, until it finally switches over to a pure tax credit system with no direct use in the market.

Principles of Economics, Chapter VIII-1 The Nature and Origin of Money:

“..(if) a good receives the sanction of the state as money, the result will be that not only every payment to the state itself but all other payments not explicitly contracted for in other goods can be required or offered, with legally binding effect, only in units of that good. There will be the further, and especially important, result that when payment has originally been contracted for in other goods but cannot, for some reason, be made, the payment substituted can similarly be required or offered, with legally binding effect, only in units of the one particular good. Thus the sanction of the state gives a particular good the attribute of being a universal substitute in exchange, and although the state is not responsible for the existence of the money-character of the good, it is responsible for a significant improvement of its money-character.”

Hans Sennholz - The Monetary Writings of Carl Menger (1985):

He was greatly alarmed by the fact that the guilder’s purchasing power exceeded the metal value of the silver guilder, which to him was an “economic anomality” harboring “the greatest dangers to the Austrian economy.”

After government has displaced private money, economic understanding of the money process will by necessity be very low. If the citizenry would understand it, they would not accept it. Furthermore, a whole generation may grow up thinking money is a purely governmental institution. Government creates tickets, which appears to be the sole reason for its value. Taxation is regarded as taking a portion of something that already has value.

This misunderstanding will get some to think they can create their own money that has no direct use. They understand that creating more of something lowers its individual value, so they think as long as something is limited, it is suitable as money. And this is how the Bitcoin phenomenon was born.

This is not to say indirect exchanges are not possible with Bitcoin, as indirect exchanges are possible with anything, provided you can sell it later on. With a market money or a government money, you are basing your acceptance and price speculation on usage. With Bitcoin, you are basing your acceptance and price speculation on future buyers who believe in Bitcoin as a money, and who further expect to find yet another person. This pricing by economic ideology and popularity is extremely volatile, which makes it a bad money.