Published: Jan 26, 2011

We start with the premise that the widely shared beliefs in a society are:

In a small village this could work in a straightforward manner, where people all know each other. If you did something bad everyone would learn about it, which would cause an immediate backfire and you would have to make things right or become an outcast. What is relied on here is the reputation of someone, which describes their trustworthiness.

Knowing the reputation of members of the society by memory is possible in a small village, but becomes quickly impossible as the society becomes larger. It also becomes more complex. For example: one person has agreed to make a delivery at a certain time but is delayed two hours because of a heavy storm. Who now owes what to whom? Or: there is a rich person with a lot of resources and a not so rich person who wants to trade his labor. How does the little guy know that he will be treated fairly? Who does he go to if his overtime isn’t paid? Remember, there is no government in a voluntary society.

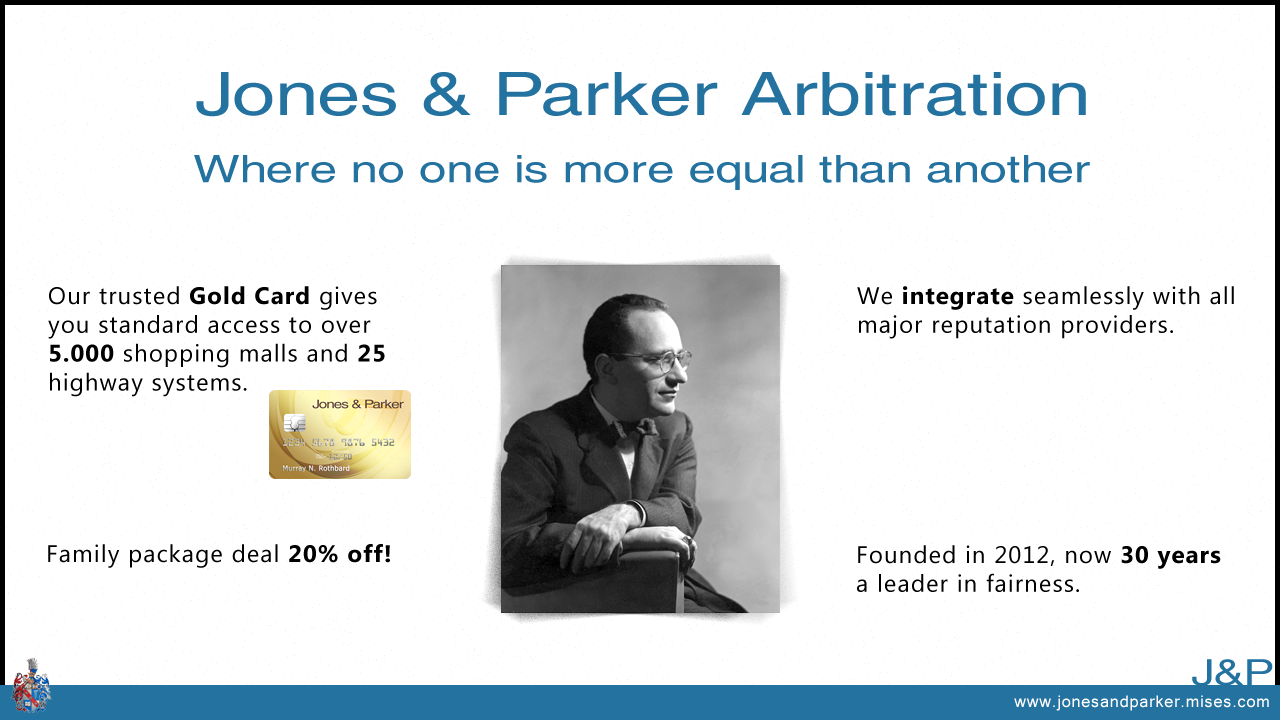

Luckily, we can foresee problems. In a market where there is no government, it is a valuable asset -competitively speaking- to be able to show your potential business partners that you can be trusted. You set yourself up to be checked, and if you don’t follow through then you lose that asset that allowed you to be trusted.

One way in which this principle could be formalized and professionalized is as follows:

You pay a business for a special kind of database service. With this service you have the ability to create permissions to add an entry, to create permissions to read the database, but no possibility to change or remove entries.

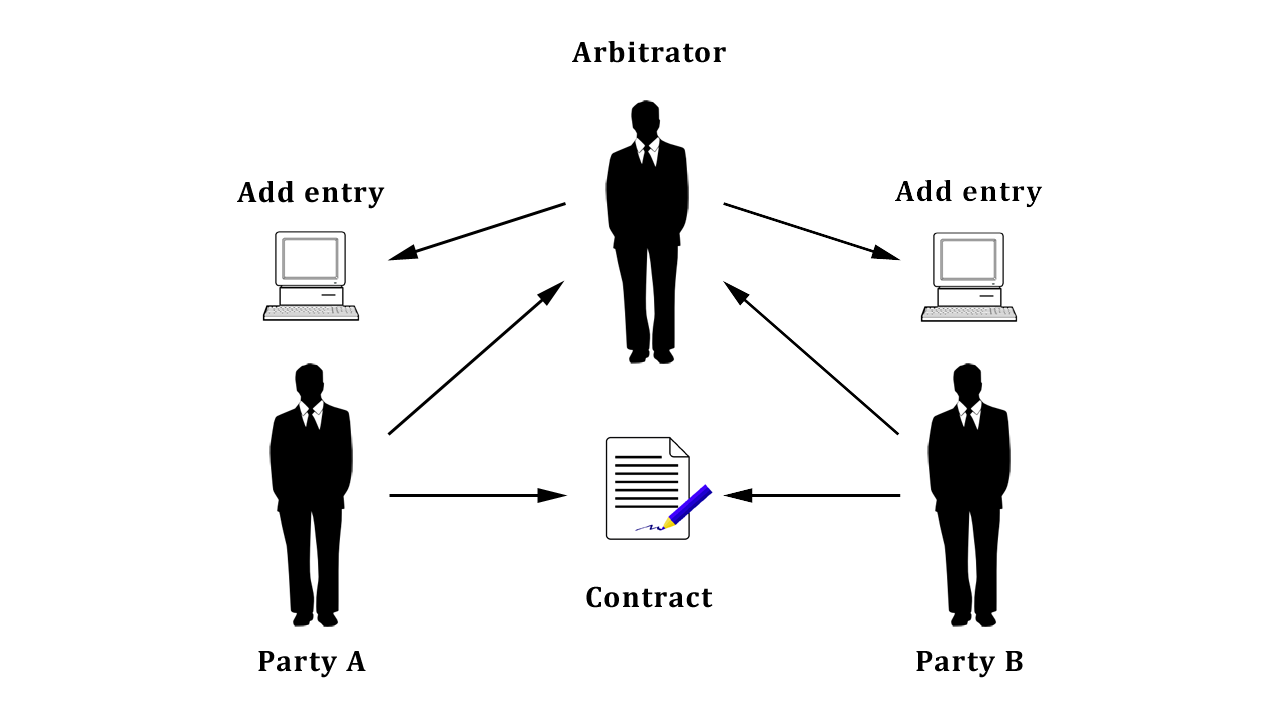

The next step is when you engage in a contract with someone, that you agree on an arbitrator (who is also paid) who will interpret the actions of the parties according to the contract in case of a dispute. The arbitrator gets an access code to make an entry in the databases of the parties. If there is a dispute and the arbitrator decides against you, and you are not willing to comply with the ruling, then the arbitrator will put his findings in your database. This means that you no longer have a way of showing potential trading partners that you are trustworthy; at least until you make things right. And in this market where such a proof has become the norm, you will be at a great disadvantage. Trading partners also require from each other that the arbitrator keeps a publicly accessible list of the unresolved disputes by way of the details of the violator and the full details of the case.

People can’t just get a new record when they’ve done something bad, because a record that doesn’t go back far is more a proof that someone is trying to hide something. In the same way, a record hosted by a provider that people can’t verify is reliable is of little value.

Personal records are very important, so providers have to make sure there are multiple online, offline and offsite backups; making them impervious to natural disasters and crime.

People will only agree on arbitrators that they trust, because they don’t want to be judged unfairly. People will also want arbitrators that are trusted by many other people, so that a strike in the other person’s record will have a big impact, lowering the risk of being cheated by the other party. Another differentiating factor is the knowledge the arbitrator has about the specific kind of business that is being done. A dispute about farm animals requires a different set of knowledge than a dispute about microchips. The only way to get a good idea of the behavior of an arbitrator and their performance in a specific field is that they give insight into the cases that they’ve handled before. They could make the cases anonymous or give people a discount to be able to publish it, and cases where someone doesn’t go along with the ruling get published anyways. Consumers also have a need in being able to make their case public themselves (with possible extra evidence) if they think they’ve been wronged by an arbitrator. Independent organizations could facilitate in all these functions so that people can find out about arbitrators, their specialties, their performances, their prices, and to keep them in check.

The career of an arbitrator is thus built on making sound judgments and in a voluntary market will face a quick ruin if they stray from this.

The above described system deals with persons and property, but only that property which is mutually recognized. Both parties can perceive to have benefit from a trade and at least temporarily agree on what property is who’s and what limits of behavior exist (for example, before you go into a car showroom you contract that the store and the goods there are not yours and that you will pay for any accidental damages). So what happens when two people have a disagreement about property outside of contractual agreements? Suppose two businessmen want to do mining in the same area, but one of them is using an entrance with his equipment and the other one wants to pass. Do they draw their guns? What is the solution? Who is actually right?

In a same manner as before, these problems can be foreseen. And because they can be foreseen we come to expect certain proofs and procedures to be adopted to handle the situation.

Society at large does not want people to take property that does not rightfully belong to them. So in the case of land, to gain legitimacy in the public view in case of a conflict, you pay for an independent and trusted service of verifying and filing what you have done to the land and when.

If you have publicly trusted records that you built a house somewhere 20 years ago, and some other person shows up who declares it is his yet he has no verifiable and trusted record of this, then we can safely conclude that the second person is either a criminal or deranged. A protection agency would in that case also be willing to draw arms if necessary, to protect the legitimate owner. This is also to say that a protection agency cannot simply sell its services to any buyer in any way because they too are scrutinized by the public. If they are viewed as being above-the-rules mercenaries, criminals, they become the opponent of the entire society, which has many more guns, resources, manpower, and are all cooperating.

In the mining example there is no clear criminal. This means that resorting to strong arm tactics would be highly suspect. Because it is easy to see that this kind of non-contracted dispute can also occur it becomes expected from people engaging in new land use to have a predetermined and knowable list of arbitrators that they are willing to use in such a case. As different fields have different arbitrators specializing in them (farming, drilling, mining, etc), there will be suitable arbitrators that are successful and respected. We expect these to occur on those lists. All of this would be the reasonable solution. If one of the two parties feels he is being treated unfairly, he will always have the trump card of going to the press and making the case public, for which there can be a high price to pay by his opponent.

How can you prove to a customer that a reputation record belongs to you? We foresee this problem and it is of very high value to us so we allow ourselves to be uniquely identifiable by our reputation provider, which becomes part of the service.

The mechanism that has been explained is one way in which a voluntary society could function. Some situations may warrant a higher investment for an even lower risk. For industrial land disputes they may settle on using multiple arbitrators from the field who decide through a vote. For contract-disputes people may want to use a tiered arbitration, meaning that the first arbitration step is cheaper and either party can decide to decline the verdict and go for the final -more precise and expensive- procedure. It is also possible that the function of reputation service and arbitration is offered as one, and it could just as well become separated even further.

Hong Kong market, 2008. CC BY-SA 3.0 Niels van der Linden↩︎

Wikimedia – Female survey crew - Minidoka Project, Idaho 1918↩︎